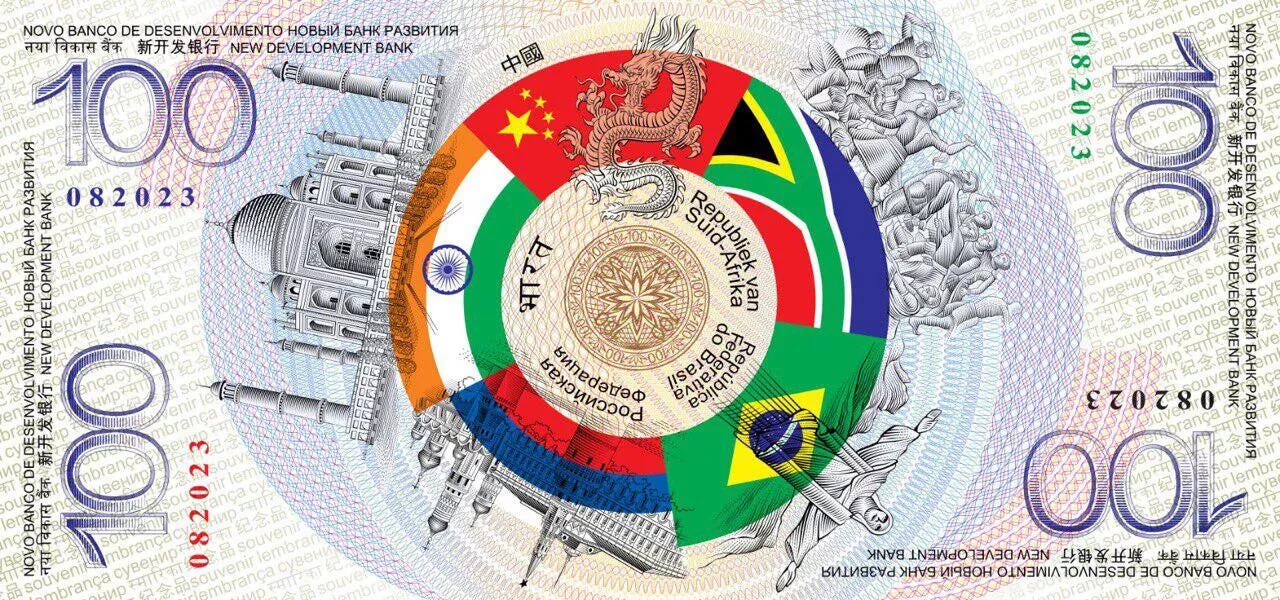

BRICS Clear Platform and the US Dollar Relic

An alternative international payments system may pave its way through monetary sanctions and USD dominance

Issuing the reserve currency of denomination and the international mean of payments provides an ‘exorbitant’ privilege, especially under the international fiat money regime in place since the disbandment of the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1971.

© Photo : Kirzhach Typography joint stock company. Source: Sputnik Globe

Foreign countries willing to pay for their imports need to get that currency to pay. And foreign countries willing to be paid for their exports end up holding that currency after being paid.1

Indeed USA - which holds this privilege - may lend its currency to those countries and act as the lender of reference for international trade, as well as pay for US excess imports - US trade deficit - with the currency that other countries need. At the same time, the US recycles its currency held by foreigners around the world by issuing the reserve asset of reference, the US Treasury bonds (T-bonds). An international demand does exist because holding US Treasury securities - which earn some return - is better than holding US cash equivalents without return. In this way, USA gets a sort of ‘free lunch’ on imports and the US interest rate becomes the benchmark return for international financing and investing. US policy-makers are well aware of this privilege and pledge to maintain it.2

BRICS countries have been taking initiative to challenge this status quo in international finance. International trade volumes and patterns have been growing within emerging countries, while monetary flows among them remain dominated by a third party currency (mainly the USD). At the same time, emerging countries savvy national currency sovereignty, they have been worried by the USD system weaponization through sanctions and burdened by material transaction fees and time delays in payments settlements.

Last October in Kazan, BRICS agreed to study not a common currency but an alternative international payments system called BRICS Clear:

[Point 65] … We recognise the widespread benefits of faster, low cost, more efficient, transparent, safe and inclusive cross-border payment instruments built upon the principle of minimizing trade barriers and non-discriminatory access. We welcome the use of local currencies in financial transactions between BRICS countries and their trading partners. We encourage strengthening of correspondent banking networks within BRICS and enabling settlements in local currencies in line with BRICS Cross-Border Payments Initiative (BCBPI), which is voluntary and nonbinding.

[Point 66] … We agree to discuss and study the feasibility of establishment of an independent cross-border settlement and depositary infrastructure, BRICS Clear, an initiative to complement the existing financial market infrastructure.

[Point 67] We task our Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, as appropriate, to continue consideration of the issue of local currencies, payment instruments and platforms and report back to us by the next Presidency.

[Point 68] We recognise the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) being an important mechanism to forestall short-term balance of payments pressures and further strengthen financial stability. We express our strong support for the CRA mechanism improvement via envisaging alternative eligible currencies …

(Kazan Declaration, XVI BRICS Summit, 23 October 2024)

Their decision was based upon a BRICS Chairmanship Research titled ‘Improvement of the International Monetary and Financial System.’ This document criticises ‘the fundamental shortcomings and destabilizing potential that stems from excessive reliance on a single currency and centralised financial infrastructure’ (Point 1, Executive Summary),3 arguing for a BRICS Cross-Border Payment Initiative (BCBPI) and a BRICS Clear platform in addition to existing international depository institutions. Four overarching principles were advocated for this set of international financial arrangements: Security, Independence, Inclusion and Sustainability.

Among BRICS countries, Russia is a commodities-exporting country which is currently forced to find monetary alternatives to the USD due to sanctions; China is both a global main exporter (for manufacturing products) and a global main importer (for commodities), willing to diversify its foreign securities holding and to increasingly use its own currency for denomination of international trade and investment. In this context, the document recalls some (unfulfilled) promises of a global financial safety net established through the IMF and its Special Drawing Rights (SDR), arguing against the interest-bearing nature of the SDR (when drawn), lending conditionalities, and the overwhelming influence of advanced economies.

In fact, a network of global commercial banks that can conduct cross-border transactions in local currencies - other than the USD - is already under development and bilateral central bank agreements to swap local currencies do already exist, although available statistics on this matter are incomplete and biased by speculative financial flows disconnected from real-economy trade and investment. But the document is more ambitious in proposing a multilateral arrangement in which money obtained from a bilateral trade with one member country may be spent to trade with or invest in another one, which was not involved in the original trade. Although the document does not preclude or preconise any practical solution, a preference appears to emerge in favor of a network of central banks managing the cross-border platform on behalf of domestic member institutions. Wholesale central bank digital currencies (w-CBDC) may facilitate platform management as exemplified by the BRI projects Dunbar and mBridge.

So far, this proposal develops a comprehensive approach which includes reforming the IMF (with the 17th General Review of Quotas (GRQ) horizon in mind), reinventing Bretton-Woods-like institutions among the BRICS, and replicating the USD system including a ‘sufficiently liquid market of available fixed income instruments in the selected currency to serve as an investment vehicle (similar to T-bonds)” (ibid., p. 38).

One problem is that ‘this approach for a reduced role of a single currency as a core FX reserve component effectively rests on a notion that a partially liberalised capital market is needed,’ (ibid.) a capital account liberalisation which has been consistently rejected by China.4

Is capital account liberalisation required to organise a faster, low cost, more efficient, transparent, safe and inclusive cross-border payment platform? Is a hegemonic currency required for an international monetary order to subsist?

Between 1980s and 2000s, the USD system has been a (temporarily) effective way to restore and maintain the USD-based exchange standard established by the Bretton Woods Agreement. As a matter of fact, the latter did not require capital account liberalisation while it sought imposing USD convertibility in gold in view to restrain the reserve currency issuer behaviour (credo No. 1). Its reorganisation since 1970s fostered a misplaced belief in the magic of unfettered global financial markets (credo No. 2), emerging countries being well aware of their nefarious impact on economies and societies. All together, US geopolitical dominance and a ‘barbarous relic’ (J.M. Keynes, A Tract on Monetary Reform, 1923: 172) found their place into an unstable and fragile international financial regime.

In the aftermath of the North-Atlantic Financial Crisis of 2007-08, shall we doubt both credos? From this fresh perspective, a multilateral payments platform across central banks may not require a safe asset but a common unit of account. Bilateral swaps among central banks do already suggest an alternative organisation in which convertibility and related interest charges (if any) may be made autonomous from financial market exposures. In the same line of reasoning, borrowing mechanisms proposed by J.M. Keynes at Bretton Woods could have made both creditor and debtor countries paying for their respective financial exposure to an International Settlement Union (rather than an international monetary fund), a non-market instrument which was not retained in the aftermath of the WWII.

While cross-border (current account) payments may be managed through innovative non-market multilateral agreements, alternative arrangements may be developed to foster cross-border real-economy investments (capital account) including by recycling outstanding trade credit positions. And a truly alternative international payments system may then find its way to complement and compete with the existing USD system.

A BRICS currency project shows dedollarisation in its making

Triggered by new international trade trends and the weaponization of the USD through sanctions, a new inter-national trade settlement architecture is under development among the BRICS countries including China, Russia, India and Brazil.

To be sure, countries do not and cannot pay. For sake of simplicity, we relinquish to the widespread and quite misleading personification of countries, whose nickname stands for a posse of varied entities located under that jurisdiction.

The US Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS) uses Fedwire (the US Federal Reserve’s real-time gross settlement system) to settle USD denominated transfers from member institution accounts at the Fed to the CHIPS account at the Fed. The US central bank provides indeed the book-entry system which backs and enacts CHIPS.

China’s position may evolve on this matter, but the current policy consists in disentangling domestic transactions from cross-border and off-shore ones (See also SAFE news 2020).